If You’re Skipping “Castle of Cagliostro” In Your Miyazaki Marathon, Don’t Talk To Me

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is often cited as the “first” Studio Ghibli movie, which isn’t true (that honor falls to Castle in the Sky) but it isn’t difficult to understand how it earned that distinction. Besides the fact that it was dubbed and occasionally distributed by Disney bundled with other Ghibli films, it’s the first in Hayao Miyazaki’s filmography that’s a 100% “Miyazaki” brand work - based off a manga he wrote, with all the traditional Miyazaki accoutrement. It could be said that Nausicaä is the first film from Miyazaki, the auteur, but it is not the first from Miyazaki, the director.

Before Miyazaki was Miyazaki, he and fellow Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata (the director behind Grave of the Fireflies and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya) cut their teeth in television animation, most notably working together on Lupin the Third Part I, an adult-oriented anime from the 70’s based off Monkey Punch’s manga. You can kind of see the seeds of his trademark style in his television work, but his first foray into film directing, Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro (or just The Castle of Cagliostro, usually), is not only one of his most influential films, but bizarrely, also probably his most obscure, at least in terms of mainstream culture.

You would think that Cagliostro would come up a little more, given that it’s about as good as a directorial debut one can possibly ask for, but more often than not, people who aren’t complete film nerds (speaking as one such nerd) usually view Miyazaki’s career with Nausicaä as the starting point. Maybe it’s because it wasn’t included in the wave of Ghibli films dubbed and distributed by Disney following Spirited Away’s success (before you ask, definitely likely because of copyright reasons rather than any fears over questionable content: keep in mind that Pom Poko, aka the one with the giant expanding raccoon scrotums, received a Disney dub and DVD release) nor the annual “Ghibli Fest” theatrical rereleases, which often include Nausicaä. Up until fairly recently, it was something one had to seek out if they wanted to watch it, moreso than the rest of the Studio Ghibli library pre-HBO Max - and even now it sits separately from that library, having found a home on Netflix instead.

I think what wards casual viewers away from this one is that it is the lone Miyazaki work which still exists within the canon of another franchise: Howl’s Moving Castle and Ponyo are also adaptations, sure, but a) of literary sources, rather than something primarily within a visual medium and b) are both pretty divorced from their source material already. They’re more adaptations of the premises of these stories than they are the works themselves. Castle of Cagliostro, on the other hand, is wedged right in the middle of a big ol’ anime library with 50 years worth of content, which is daunting to say the least. How much do you need to know about Lupin the Third to engage with this film?

Here’s the thing: you really don’t.

Weirdly enough, I’d compare this to The Spongebob Squarepants Movie, of all things: a film designed with the intention of being a narrative finale for its lead, even though the franchise proper continues beyond it. Neither film requires that you come in with any background on who these characters are, but with or without that context you still have a satisfying, fairly complete viewing experience. Knowing the history might make it slightly more meaningful, but speaking as someone who went into it blind the first time, you won’t be asking why you should care if you don’t.

And much like The Spongebob Squarepants Movie, the cartoony cast of this film is extremely adaptable, something that seems to have heavily contributed to the franchise’s longevity. It’s interesting to watch the way Miyazaki works with characters who he may not have created, per se, but has a great deal of experience with.

Lupin (or Wolf, if you’re watching the Netflix dub — something something 90’s copyright reasons) is an anomaly in terms of Miyazaki heroes in that he’s morally cast in shades of grey: he’s a bit more impish, a well-meaning mischief-maker, but with a good heart and caring nature beneath his philandering and showboating. He’s a thief, but that isn’t necessarily a fault in his character he needs to fix - if anything, the film confronts the fact that he simply can’t. To be fair, the world these characters inhabit is a little more accommodating to that lifestyle than, say, the war-torn countryside of Howl’s Moving Castle or the polluted seaside town of Ponyo: this is a universe where the cat and mouse game Lupin and his gang play with the police could feasibly go on forever, where adventure and treasure can always be found if you’re looking. The kind of happily ever after most Ghibli leads settle into simply doesn’t offer him anything fulfilling, as much as he’s tempted to try.

It’s actually kind of crazy how unusual these characters are as leads in a Miyazaki film, and how well they fit with his style in spite of that. All of our main characters, with the exception of the gentle princess Lupin needs to save, genuinely enjoy their lives of crime. They’re friendly enough, if a little rough around the edges, and really only better than the titular Count Cagliostro (one of the few straightforward villains in the Miyazaki canon) by virtue of not crossing the line from criminal behavior to being outright abusive. Even the inspector hounding Lupin across the globe is less of an antagonist and more of a gruff, irritable dad trying to rein in his shithead kid, the Tom necessary to give Lupin’s Jerry a decent chase.

And speaking of - we gotta talk about the car chase.

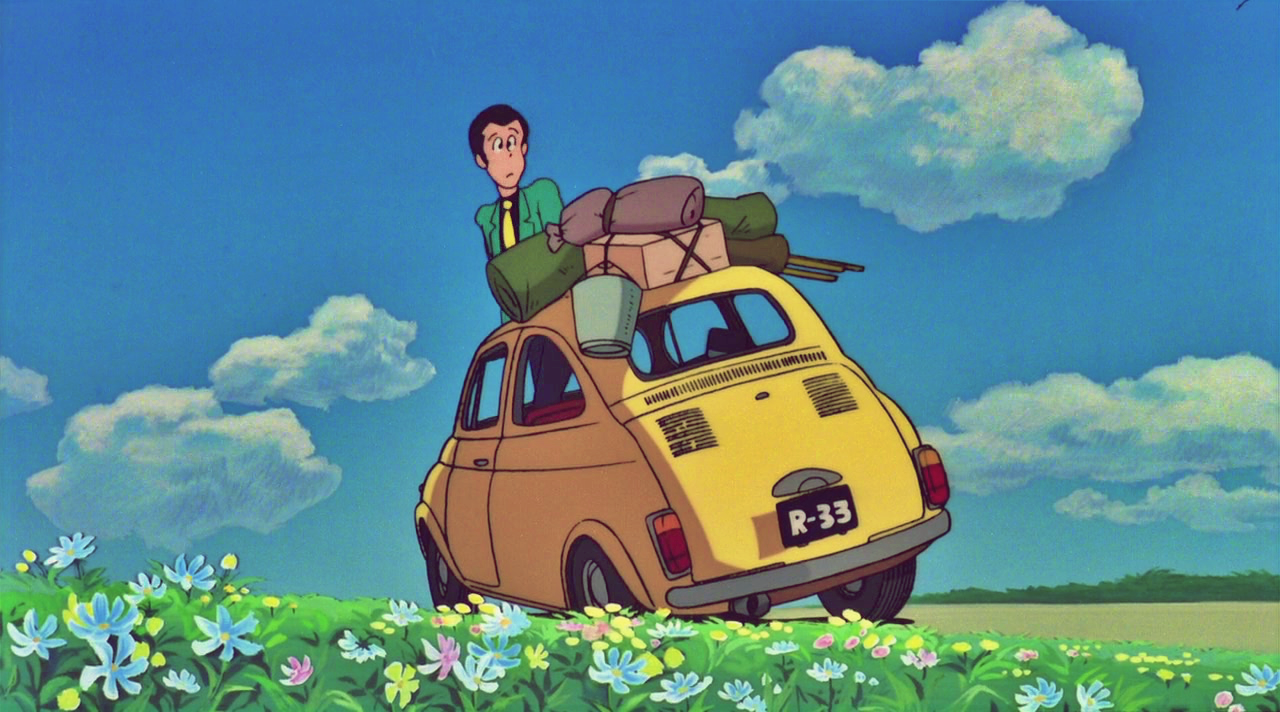

So there’s this urban legend that Steven Spielberg, after seeing Castle of Cagliostro at Cannes, cited the opening car chase as one of the best ever put to film. Either that, or he said the film as a whole was one of the best adventure movies of all time. There is no evidence to support either claim literally anywhere, as much as I desperately want at least one to be true, but what we do know is that a whole lot of Disney animators (and future Pixar animators) in the 80’s saw this movie and pilfered the shit out of it. Big Ben fight at the end of The Great Mouse Detective? Cagliostro. Waters receding from Atlantis once it rises from the bottom of the ocean? Cagliostro. Batman: The Animated Series, The Simpsons Movie, Ducktales - cultural icons all deliberately pulling some form of influence from this film. But the big sacred cow is the car chase, and in fairness, it’s not hard to see why. The choreography is kinetic, the music pops, and the weight and speed of it all is - well, some of the best ever put to film. Plus, it’s just fun to watch this dinky little Fiat zoom around a narrow road, tilting every which way and literally drifting up a cliff. It’s brilliantly paced, fantastically energetic, and chock full of those little details that make Miyazaki’s films so distinct.

If you’re looking for a point of comparison between Cagliostro and the rest of Miyazaki’s filmography, narratively I’d put it closest to something like Porco Rosso or Castle in the Sky: a fairly light adventure/mystery film with stretches of quiet, character driven drama between dynamic action set pieces and comedic sequences. It’s a bit zanier than Castle in the Sky, a little less thematically dense than Porco Rosso, but that’s “less thematically dense” by Miyazaki standards: you’ve still got your condemnation of greed and your examination of the journey into maturity so many of his younger protagonists face. It’s just that this time, the mature, responsible decision is to leave the starry-eyed princess behind and continue a life of crime.

Really, it’s fascinating to watch a Miyazaki film that feels so youthful and maniacal, with echoes of his future career scattered all throughout it. Princess Clarisse’s planetarium-inspired bedroom bears a striking resemblance to the nursery of Yubaba’s giant baby in Spirited Away; Clarisse herself has a very proto-Nausicaä look to her, and her quiet resolve brings Howl’s Moving Castle’s Sophie to mind; even the cuddlier interpretations of the Lupin crew seem closer to the sky pirates from Castle in the Sky than their usual cutthroat selves, a band of merry thieves with gruff exteriors and big hearts. And of course, all the regular hallmarks of a Miyazaki film: wide landscape shots, intricate machinery, food that looks impossibly squishy and round and appealing, characters who run Like That, “Ghibli Hair,” and a reasonable, if slightly indulgent, number of planes.

If anything, this is one of the more actively rewarding Miyazaki films in the long term because if you want more of these characters and these adventures, there is an overwhelming wealth of content you can delve into at your leisure. Even if Miyazaki’s interpretation of Lupin is a little more romantic than the rest of the franchise, you can kind of pick and choose how much darker or weirder you want to go, if at all. You can’t say the same for Kiki’s Delivery Service or Princess Mononoke, and you wouldn’t want to: they’re contained. They’re Miyazaki’s stories, told precisely how he chooses to. This time around, however, he’s playing with someone else’s toys, so it’s not really his place to tie everything up in a neat little bow.

There’s something kind of exciting about that sort of “and the adventure continues” ending when placed beside the rest of Miyazaki’s work, something you don’t really get when you start with Nausicaä - a piece that feels like it was made by a master of his craft, already the lovable old curmudgeon we know him as today. Cagliostro is shaded with the confidence and tepid optimism of a future auteur really stretching his wings for the first time, someone who didn’t know he was already rewriting the game.